Panic attacks represent the worst form of anxiety. Anxiety creates an almost permanent feeling of hyper-vigilance – a state of perpetual concern where uncertainty and feelings of threat and fear are never far away.

Panic attacks are the point at which anxiety bubbles over, creating feelings of unbearable fear, feelings, which at the time of the attack seem like a fate worse than death. And so the one enduring the attack feels helpless, hopeless and unable to reclaim control. For many sufferers even when the attack is over, they return to an underlying anxiety, as they await the next attack, believing it never to be too far away.

Those of you who have ever suffered an attack, will know that there is no feeling quite like it and you would do anything for relief and better still a permanent solution. Does such a thing exist? Let us explore this subject and help you to find what is the best antidote for you.

What causes panic attacks?

There are many theories on the causes of panic attacks. Here are the four theories that, based on our clinical experience and research, we consider to have most relevance and value:

1) Some scientists and mental health professionals consider there to be a genetic factor that makes some individuals more prone to panic attacks under certain environmental conditions. Given the power of our genetic inheritance, this conclusion certainly has validity, as we all come with a set of genetic predispositions. It should be said, however, genetic predispositions do not mean we are tied to a particular fate – it simply means we have more of a ‘leaning’ in a specific direction. The epigenetic revolution is highlighting our ability to liberate ourselves from our familial inheritances, as it has more accurately defined the relationship between nature and nurture. See: Epigenetics – We are more than our genes.

2) Many social scientists and psychologists consider an individual’s upbringing to be the single biggest factor in the development of anxiety disorders. This is because we are the net result of our life experiences. In our formative years if we are not offered an adequate template for dealing with the ups and downs of life (particularly the downs) then we don’t have a healthy ‘go to’ position when things do not play out as we expect or hope. Where there has been a lack of The 3 A’s (attention, affection and affirmation) the child is ill-equipped for the challenges of adolescence and adulthood.

3) Sustained stress is another major factor in the development of panic attacks. From our extensive experience of working with this issue we have observed that often in the year preceding the panic attacks, most individuals were enduring sustained and often unimaginable levels of stress. If we think of panic attacks occurring at the point when our personal capacity has been reached, then it’s not surprising that if the individual is relentlessly exposed to stress, they will reach that point of being unable to cope more quickly.

4) There can also be physiological reasons why someone is experiencing panic attacks. For example: an overactive thyroid gland (hyperthyroidism), low blood sugar issues (hypoglycaemia), and minor cardiac problems (mitral valve prolapse – this is when the heart valves don’t close correctly). Each of these conditions could be a reason for the individual’s episodes of panic. So, if you have any physical concerns about your health, it is probably worth seeing your GP, to eliminate such possibilities.

It’s also worth mentioning that stimulant use (amphetamines, caffeine, cocaine etc.) can also generate panic attacks, as can various medications – with their numerous side effects. Medication withdrawal, especially when not managed appropriately, can also be a trigger.

What are the common symptoms?

The symptoms of panic may manifest differently in each person. These attacks often come suddenly and without warning. However they do have a pattern but for many sufferers, that pattern is lost in the fog of their symptoms. So many sufferers are not sure what the triggers are, which can make the condition very difficult to treat.

The list below contains the common symptoms most frequently reported but this is not a definitive list, nor would a sufferer expect to experience all of these things. It is much more likely that one or two of these symptoms may be experienced by the individual and not necessarily the same ones each time.

Difficulty breathing

Hyperventilation

Pounding heart or chest pain

Intense feeling of dread

Sensation of choking or smothering

Dizziness or feeling faint

Trembling or shaking

Sweating

Nausea or stomach cramps

Tingling or numbness in the fingers and toes

Chills or hot flashes

A fear that you are losing control or are about to die

The experience of a panic attack can last anywhere between five and twenty minutes with the average attack being about ten minutes long. However for the sufferer that period feels like a lifetime. This is why such episodes can be so exhausting – physically and mentally.

Those who experience panic attacks with some regularity are described as having a panic disorder. In these cases, even when not experiencing an actual attack, the sufferer spends much of the time anticipating the next episode, which often brings an attack on – therefore creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. This anticipatory attitude can cause substantial physical, emotional and psychological problems, as the neurochemical consequences on the brain and body of on-going anxiety and panic are significant.

Below is a brief overview of some of the biological events and consequences…

What is actually happening?

There are many theories about what is actually taking place during a panic attack and the discussion and debate continues. What we do know is that the limbic system is a key player in relation to anxiety and panic.

The hypothalamus, one of the key structures in the limbic system (the emotional centre of the brain) regulates responses such as ‘fight, flight or freeze’. It also controls the release of hormones and neurons affecting heart rate and respiration and is responsible for many of our homeostatic bodily functions, such as temperature and circadian rhythms. The hypothalamus is often referred to as the ‘mood centre’ – and one’s mood has a significant impact on all these vital functions.

The amygdala, also part of the limbic system, regulates behaviour and is primarily involved with emotional processing. The amygdala interacts with the prefrontal cortex (where the orchestration of thoughts and actions takes place and other executive functions) generating and processing major emotions such as: anger, happiness, disgust, surprise, sadness, shame and particularly fear. It is clear that the amygdala has a special role in keeping us safe, by being sensitive to fear and its consequences, which is why it is a key player in the story of panic attacks.

The hippocampus is another structure within the limbic system that is highly relevant to what is going on when we are under the influence of anxiety states and in the grip of panic. The hippocampus is responsible for the formation, storing and organising of memories. It receives its primary inputs from virtually the entire neocortex (the crinkly surface that you see in pictures of the brain), which enables it to link together seemingly unrelated information and data and bring context to what it is we are seeing, feeling and experiencing. It is this particular ability to contextualize that makes the relationship between the amygdala and hippocampus a crucial one.

All three structures communicate with the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain most linked to our personality, which is why these three structures are very susceptible to our thoughts, moods and feelings.

When the hypothalamus, amygdala and hippocampus are working optimally and in harmony, we are able to process thoughts, feelings and emotions without being disproportionately disturbed or affected by them – in other words, we respond rather than react. However, when these highly sensitive structures are stimulated in ways that provoke anxiety and fear then they conspire as best they can to keep us safe, they adopt a ‘survival stance’. This is where many of the problems begin.

As negative data/experience comes in via the hypothalamus an emotional calculation, based on past experience(s) takes place, which determines the fight, flight or freeze response. According to that calculation, which is influenced by the amygdala there is a withdrawal of energy from the rest of the body (our extremities) and the body moves into a ‘shutdown’ mode – a position anticipating a threat/attack. Simultaneously, the hippocampus, based on all the data it is drawing via the neocortex, is trying to give the episode/experience context, therefore helping to make sense of what the individual is being exposed to.

If the mind-body system has had sufficient reassurance in the past, then in the face of threat, there is the underlying belief, ‘all will be well’. In the absence of that reassurance, rather than a harmonious exchange of data between these structures, leading to more healthy and positive responses, each structure acts in its own self-interest (survival mode). The problem with this is the individual is taken on a rollercoaster ride of fear and disproportionate reaction follows and panic then ensues. This has come to be known as the ‘amygdala hijack’ where the rational response has been overturned. In this scenario the hippocampus has not been able to provide context swiftly enough to overturn the biological and emotional responses.

The hypothalamus at this point in the push and pull of events, continues to maintain hyper-vigilance, which leads to the overproduction of adrenaline and cortisol, via the HPA axis (Hypothalamus, Pituitary, Adrenals). So a vicious cycle is created and the individual becomes a victim to events. It is this vicious cycle that needs to be broken to return power and control back to the person suffering. See: Brain Matters.

What treatment options are available?

Although it’s often difficult for the person suffering from panic attacks to believe that they will ever end, it should be underlined that this is a condition that can be completely treated and resolved. Unfortunately a one-pronged approach is often used, where a more holistic strategy is needed. This is why far too many sufferers find they cannot break free of their nightmare.

The main treatment options include:

1) Medication – there are numerous options here often classified as anti-anxiety medication, such as: Xanax, Ativan, Klonopin etc. These medications are not designed for long-term use and so if that has been your experience, we would suggest discussing this with your GP as it may be better to consider other more effective medication or strategies.

Certain antidepressants can also help with preventing anxiety and reducing the frequency and severity of panic attacks. The ones most commonly prescribed are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as Prozac, Zoloft, Lexapro, Paxil and Celexa. For those seeking a medical option, this group of medications is often considered the first line of treatment for panic attacks/disorders. Again one should be aware of long-term use and the potential side effects.

For those who wish to explore the use of medication as a treatment option for anxiety and panic attacks, it’s well worth checking out the work of Professor Irving Kirsch, who’s made a valuable contribution to the debate on the use of antidepressants. See: The Emperor’s New Drugs

2) Counselling/psychotherapy – talking therapy is such a broad church, that finding the right therapist and treatment programme can actually add its own stresses and strains because the profession does not always agree on what works best, which leaves the client/patient unsure whether they should pursue a person centred way of working, or a psychodynamic approach, or something more integrative (drawing together a few therapeutic schools/approaches and applying them in a complimentary way). So how can a client choose when they have so many choices and options? We will come back to this point when we discuss ‘The Story of Health’. See: Are Talking Therapies Sufficient?

It should be stated that in some cases counselling/psychotherapy alone can clear up panic disorder. CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) is one school of psychological therapy that is being promoted by many mental health professionals believing it to be the best strategy. It should be said that the research is ambiguous and we would state that CBT can be a very good intervention but should not be seen as a panacea. 1,2

CBT essentially helps the individual to learn how to deal with panic symptoms by teaching the client/patient that their thoughts of impending doom are actually based on irrational beliefs – a false alarm. By actively and gradually exposing the individual to situations that trigger feelings of anxiety and panic, usually in the safety of the therapeutic setting, the therapist helps to desensitise the individual to the triggers and events that cause their emotional disturbance. This ‘virtual’ exposure can and does work very well. Some therapists also combine this approach with teaching conscious breathing and muscle relaxation techniques (autogenic relaxation).

CBT is also increasingly being allied to mindfulness as an effective strategy for addressing anxiety and panic disorders. This combination often works well as in both disciplines the mind is being re-educated and realigned and as a result healthy control is restored.

3) Meditation and mindfulness – both these disciplines are thousands of years old and originate in the east, namely India and China. Their long and valuable heritage is now being fully appreciated and is being applied to a range of both mental and physical conditions in the developed world. So it is no surprise to see that extensive research has now led to the development of countless educational and health programmes where both meditation and more particularly mindfulness are being employed to great effect.

Much has been written elsewhere about these two disciplines and so we are not wishing to repeat that narrative, but for those who want to explore more please take a look at: The Power of Introspective Practices.

Returning to our focus on panic disorders, there is ever-increasing evidence of how both meditation and mindfulness subdue the amygdala, offering the ‘reassurance’ that helps reduce its grip on both the hypothalamus and the hippocampus, enabling this triad to work more cooperatively and effectively. It is the soothing of the nervous system through meditation and mindfulness which impacts on the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala that enables the vicious cycle of anxiety and panic to be broken.

To explore this subject further, you might like to take a look at the comprehensive work and research around meditation by Dr Shanida Nataraja, author of The Blissful Brain, as well as the extensive research being done at Stanford University’s Centre for Compassion and Altruism, Research and Education.

If your interest is more in the area of mindfulness then you may be interested in the extensive works of Professor Mark Williams of the Oxford Mindfulness Centre and ProfessorJon Kabat Zin, who is the creator of the Stress Reduction Clinic the Centre for Mindfulness in Medicine, Healthcare and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

4) Support groups – are not for everyone, as there are many who find the idea of exploring their issues in a group anxiety provoking – and for some this would even bring on a panic attack. However, it should be said that for a significant number, groups are at least part of the antidote.

That feeling of ‘safety in numbers’, can be very empowering as one increasingly realises there are many in the same boat as them. This helps remove that feeling of isolation and the idea that something is fundamentally wrong with them – something that might be beyond repair, which is a common feeling amongst sufferers.

So sitting and sharing one’s experience with others can remove the feeling of being alone and being different and can also inspire the individual to pursue helpful strategies in a more passionate and diligent way.

There are numerous ways to access such support groups. However, if one is not confident about meeting people face-to-face then there are many online forums, where one can participate whilst maintaining some degree of anonymity. But it could be argued that this approach is much closer to self-help, when the real value of being in a support group is the human contact and that sense of belonging to something bigger than oneself, which of itself is empowering.

If this is an option that attracts you, then we would recommend researching what is available in your area and only joining groups that have a reputation for being safe, sensitive and supportive. You’re not joining a group of this kind to be confronted or to have your shame accentuated, so choose wisely.

5) Self-help – this is the area that is probably fraught with the most challenges because there is a plethora of books, articles, personalities, gurus, workshops and countless resources each promising the secret code that will unlock all the mysteries, enabling the individual to surpass their expectations and dreams.

Even though there are numerous success stories that one can point to, which support the efficacy of a particular model or approach, there are just as many disappointments where the promises made have not been fulfilled. This does not mean that individuals should not seek to help themselves – to the contrary, self-help has a critical place in all treatment programmes and it could be argued that without it none of the regimens are likely to work.

However, if you are going to take a predominantly self-help approach, we would recommend that you walk the well trusted paths – pursue those methodologies, strategies and approaches that have been recommended and well researched. Avoid that which doesn’t have good clinical evidence (has been tried and tested with real people) and look for genuine testimonials to support your choices.

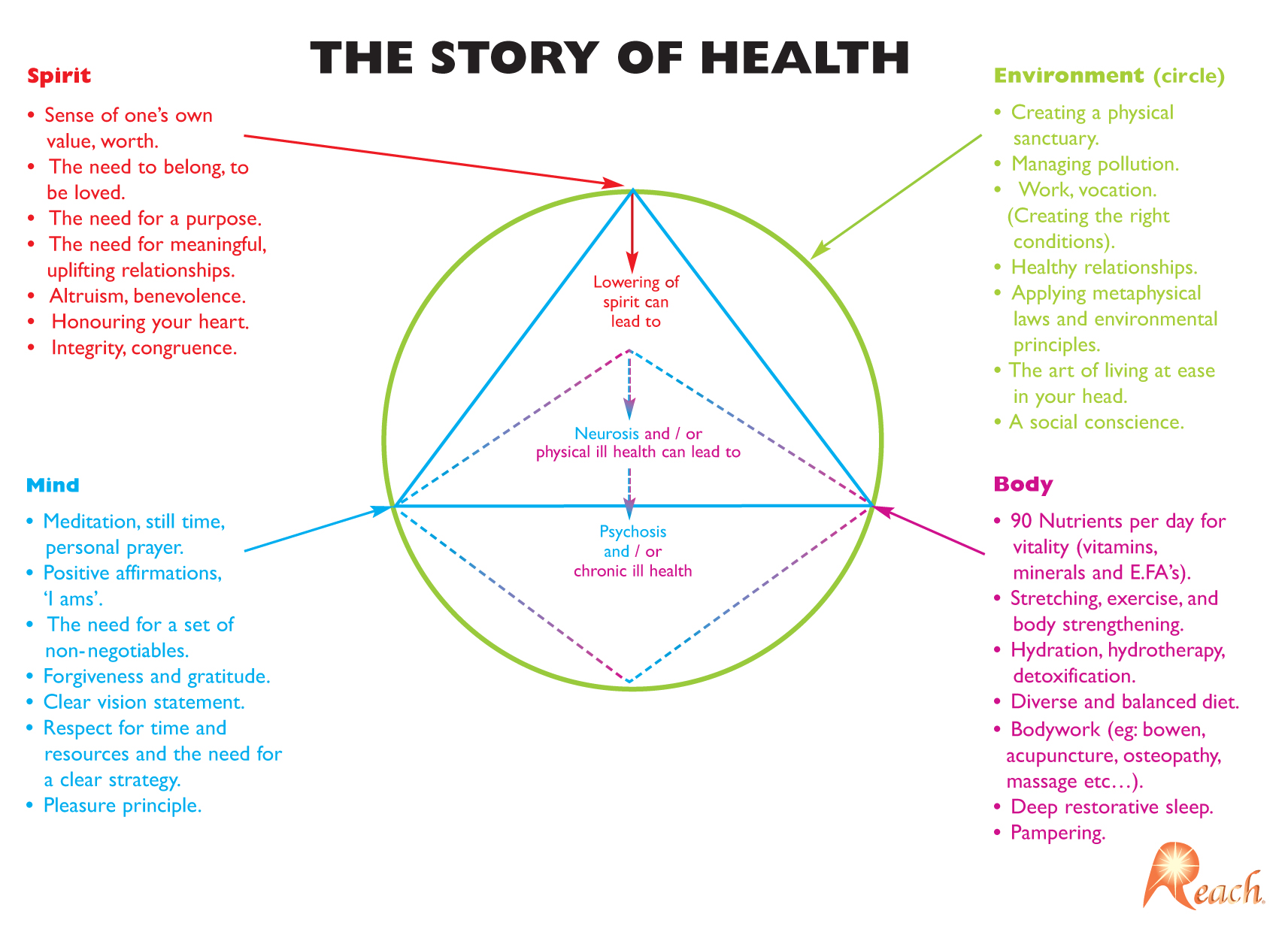

In our experience, the reason that a lot of individuals pursuing a purely self-help approach fall short, is because exploring a lot of information and data from numerous sources can in fact be very confusing, especially when one does not have a cohesive strategy that enables them to integrate all of that information. This is one of the reasons we created The Story of Health. This is a simple, all-encompassing model, which pulls together the essential principles for a balanced, healthy, fulfilled and contented life.

The Story of Health recognises that in order to be happy and healthy, one has to meet one’s needs in four key areas, which are, mind, body, spirit and environment. Without an approach that addresses the needs of each of these crucial aspects then any remedy only ever manages the symptoms and not the causes. The Story of Health is about both cure and prevention. We will come back to its importance in the conclusion.

6) Exercise is a form of medication – it is increasingly being acknowledged in the research literature that exercise is a legitimate and effective form of treatment in relation to anxiety and panic disorders. As a result growing numbers of mental health practitioners are considering it as a valuable strategy to help arrest symptoms and in all cases bring about better management of the condition(s). From the evidence collated to date yoga and tai chi have achieved the best results for those suffering with panic attacks and anxiety.3

Aerobic exercise that increases the individual’s heart rate to between 60 and 90% of their maximum heart rate capacity, three or more times per week, for between 20 to 40 minutes, has also proven to be very significant in lowering anxiety and lessening the frequency and intensity of panic attacks.4

Another effective form of exercise is resistance training three times a week, which involves whole-body workouts, which is very good at reducing what is described as ‘situational anxiety’, that anxiety that is responding to a specific place/event or moment in time. As discussed previously, if anxiety is reduced in response to particular situations and events, the individual is much less likely to experience a panic attack.

It should be pointed out that one does not need to go to the gym to experience these benefits. The value of walking, cycling, stretching and swimming for example cannot be overstated. In fact all exercise, not undertaken to exhaustion, brings a host of benefits which include: an increase of endorphins (which themselves reduce anxiety) and a soothing of the sympathetic nervous system, which means it’s less likely to overreact. Exercise also increases the neurotrophic factors (proteins responsible for the growth and maintenance of neurons) in the brain, which help to rewire the brain’s response to stressful situations. Sleep quality significantly improves too, which improves our interpretation of emotional events. Stress tolerance levels increase, making it less likely for panic to occur and where it does occur the severity and frequency are reduced. These are just a few of the many benefits derived from making exercise a part of your treatment plan.

It’s important to state, that you should always exercise within your capacity. The best results are not achieved by doing too much, in fact over exercising can be just as damaging as too little exercise… so be sensible. See: Exercise and Happiness.

The Reach Approach in relation to panic attacks

It was stated earlier in this article that we believe a one-pronged approach to anxiety and panic is a flawed strategy. In our experience those who are seeking a permanent solution actually need to ensure that they adequately meet the needs of the mind, body, spirit and environment, as outlined in The Story of Health. Below is a summary of those primary needs.

What does the mind need?

It needs a diet of positive self-nurturing thoughts, which uplift and inspire.

It needs a clear vision/mission statement so it knows where it is going and what it is trying to achieve.

It needs a set of ‘non-negotiables’ – helpful practices that sustain and support its equilibrium and evolution.

It needs stillness and silence for repair and rejuvenation.

It needs to pursue activities that cause no harm whilst promoting pleasure and joy.

It needs to forgive itself for its mistakes (and others) because without compassion one cannot fulfil one’s potential.

It needs to develop an attitude of gratitude. The more we count our blessings, the more blessings we will have to count.

What does the body need?

It needs a diverse and balanced diet. The more colour in the diet the better.

It needs deep restorative sleep – which is essential for good ‘housekeeping’ and repair.

It needs hydration, as we are ‘vertical rivers’ and nothing works properly in the body without water.

It needs regular exercise – movement is health, stagnation is disease.

It needs pampering, which means pursuing activities that are self-indulgent and nurturing.

It needs a minimum of 90 nutrients per day, to give our immune systems the best response to our toxic environments.

It needs positive self-talk. The mind and body are intimately entwined and the body does not respond well to self-condemnation.

What does the spirit need?

The spirit needs a life of meaning and purpose, otherwise it moves along aimlessly, feeling unfulfilled.

It needs to be true to itself. There is nothing quite as liberating as integrity and truth.

It needs a sense of its own value and worth. Without this the spirit is lost in the malaise of life.

It needs heartfelt and meaningful relationships.

It needs altruism and benevolence – charity really is good for the soul.

It needs to be loved and to belong to something more than itself.

It needs a sense of its relationship to time, space and the universe.

The four environments

The Story of Health diagram is a simple illustration of the relationship between the mind, body, spirit and the environment. What we can see is that the triangle sits inside the circle, which demonstrates that all three interface with and depend on the environment. In order for us to understand the needs of the environment we actually have to understand that the environment comes in different forms.

There is the environment of the self (our inner landscape – thoughts, feelings, moods etc.), the environment of the body, those 60 trillion cells that conspire to give us life. There is the environment outside of ourselves – our families, relationships, communities and society… and then of course there’s the environment of the planet, the stage on which the drama of life is played out.

Once we understand these different environments, we can begin to see that meeting the needs in each area will require different things. It’s interesting to note that although these four environments do require different resources, there is an intimate relationship between them as one underpins and supports the other. For example, meeting the nutritional needs of the body also underpins and supports how the individual feels about him/herself. Also, creating a space for silent reflection creates a calmer brain, which in turn generates a healthier body. The overlap and connections between these four environments are endless.

Here’s an overview of the environmental needs

Where possible, create a physical sanctuary, a space for reflection and self-nurture, which leads to an improved self-image and physical well-being.

Developing a social conscience is vital – creating a culture where all are equally valued and respected – family, friends, colleagues etc.

Consciously minimize your negative impact on the world – managing your carbon footprint.

Create healthy physical environments – at work and at home. Decluttering and creating order is good for the mind and the spirit.

Avoid waste in all of its forms. Waste harms the mind, body, spirit and the planet.

We need to learn to conserve energy and learn to make the most of the resources available to us.

Understanding these four environments reminds us that they each need our on-going attention and respect.

Conclusion

Hopefully you can now see from what we’ve offered here that there are many options for managing panic attacks. Firstly, we have to reduce our stress levels wherever we can. This will prevent anxiety from developing in the first place, which then makes it less likely that panic attacks will occur.

If you currently find yourself in the grip of panic, then getting support or help in a form best suited to your personality and life will undoubtedly be helpful. Finding ways to resolve issues in your past and learning to live more healthily in the present will cut off the supply of negative self-talk that often sustains anxiety and panic disorders.

It’s the negative self-talk and unresolved issues that sustain the ‘false alarm’ that has been activated in the brain. This is why activities such as talking therapy, mindfulness, meditation, relaxation and exercise can all soothe and reassure a mind that is overreacting to the external stimuli.

You’ve seen that there are numerous antidotes to panic and anxiety, each with its own merits, however, they mainly manage the symptoms, which in some cases is enough. But our recommendation is that anxiety and panic are best dealt with through The Story of Health.

In other words, identify what your deficiencies are in terms of the mind, body, spirit and environment and set about remedying them in the best way you can and there you will find your lasting solutions.

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790)

Additional References:

1. Chambless, D.L. (2002) Beware the dodo bird: the dangers of over-generalization. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9 (1): 13-6).

2. Wampold, B.E. (2001) The Great Psychotherapy Debate: Models, Methods and Findings. L. Erlbaum Associates.

3. Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Relf M. Tai Chi/Yoga Effects on anxiety, heart rate, EEG and math computations. Comp Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16:235-238.

4. Gordon J.G. et al. Let’s get physical: a contemporary review of the anxiolytic effects of exercise for anxiety and its disorders. Depression & Anxiety. 2013; 30:362-373

Also see: Anxiety Disorders